OTHER SESSIONS:

(1) The “artistic moment“ within accounts, contracts, descriptions of objects and self-portrayel in the High Middle Ages.

Jens Rüffer

Medieval work processes based on the division of labour, nevertheless the responsibility – not necessarily the execution – lay with the magister operis or the master workman. The beginnings of a artistic self-conception start there, where a portion of the wage is paid as a general gratuity for the execution itself, inscriptions referring to the craftsmen or similar symbols of status. This material remuneration or the intangible recognition honours what can be retrospectively described as additional artistic value. In northern Italy, this type of gratification became established earlier than north of the Alps. In general, the question arises as to when this phenomenon begins to occur, in which geographical regions it can be observed and in which social structure (monastery, city, court) it emerges. Furthermore, it is necessary to ask about those persons and groups of persons who decided whether and how much this “special remuneration“ was.

A large number of accounts or contracts have survived in which such references can be found (building workers, goldsmiths, carpenters, glass painters, etc.). Sometimes these documents also provide information about the work process itself, about the division of labour, in-house or external work, hierarchies within the workshop, the establishment of a temporary object-related working group or production according to oneʼs own or someone elseʼs design. These “facts“ or “realities“ can be contrasted with descriptions of objects that do not primarily follow the rhetorical strategy of ekphrasis, but describe in more detail what is experienced in the viewing. In this respect, all descriptions are interesting, even if they do not express anything about that what is considered as an “artistic“ moment from todayʼs point of view. Because this is also a statement about the contemporary perception of this kind of work. Finally, there are various medieval visualisations that depict master craftsmen or work processes, inscriptions that praise the work and/or the master, which must also be critically examined for their informative value. Older research has interpreted a lot into this.

This section is looking for contributions that critically scrutinise the above-mentioned source genres in an exemplary way with regard to the “artistic“ moment. Since northern Italy plays a pioneering role here, trans- and cisalpine sources should not be mixed without reason. However, they can be compared with each other from a socio-historical point of view.

(2) Arte-factum. Theory formation through working practice in the arts of the Middle Ages

Heike Schlie

This session will discuss how working practices, and their material and technological conditions generated the formation of art theories in various genres during the Middle Ages. Despite extensive research on the reception of works and the self-image of medieval artists, the idea persists that "craft" prevailed in the Middle Ages and "art" emerged under new conditions in the early modern period. However, it is often overlooked that the Christian Middle Ages first made a re-evaluation of the artes mechanicae possible. Their work and products were considered a partial restoration of paradise on earth. Consequently, the creation of the artes mechanicae was seen as a continuation of God's creative power. This concept integrated the artifex's expertise and the material conditions of artifact production. Materials, material effects, tools, and techniques are not contingent on the earth, but are intended by divine creation and the salvation plan to glorify God and generate knowledge of all kinds. This has consequences for both the status of the artifex and the products of the artes. At the same time, artists employed various strategies to link their work to the artes liberales (e.g. geometry: architectural drawing, optics: oil painting, arithmetic: bronze casting). Theologians theorized and allegorized the artes, materials, and techniques in their writings, resulting in a condensation of the discourse, which is reflected in the works' argumentation about their working practices. Ultimately, these allegorizations belong to theological theorems, thus generating them in the craft.

Possible topics and key questions:

· Visualization, meaning, and theorization of material and technical processes in the artifact

Artistic practical knowledge as a contribution to theory formation

Symbioses instead of dualisms of form and material, theory and practice: observations from source texts (e.g. art theory treatises, recipe books, theological writings) and artifacts

Terms and concepts from image and art theory (e.g. mimesis, perspective), metaphors (e.g. window, mirror, veil), basic categories (e.g. transparency/opacity): To what extent can these be (re)thought in terms of material and artistic practice?

Artistic self-reflexivity between theory and practice (e.g. artists' self-portrayals, Lukas-Madonna, signatures, etc.)

(3) Artists at (Municipal) Work: Image-Making and Civic Governance

Masha Goldin

What common ground existed between artistic work and the business of governing cities in the Late Middle Ages? This session seeks to address this question by examining case studies in which artistic practice and municipal regimes became intertwined. Such instances are particularly evident in the oeuvres of artists who, in addition to their workshop activity, held roles as civic officials. Examples include Tilman Riemenschneider, who served as mayor of Würzburg from 1520 to 1525, and the prolific illuminator Diebold Schilling, who acted as notary of the civic court of law in Bern from 1481 to 1515. In what ways did these dual roles inform one another? Numerous other artists held official roles in town councils as a result of their guild membership. At the same time, sculptors, painters, goldsmiths, and other craftspeople working in various media—bearing no governmental titles—were hired by municipalities to pursue artistic projects for civic ends. How did municipal patronage shape the products of the artists’ labor? What kinds of artefacts were used or produced in the bureaucratic work of town councils?

The session seeks to broaden the discussion by inviting contributions that consider proto-curatorial and urban planning practices, often carried out by municipal authorities when arranging installations of objects, such as civic insignia or loot, or when envisioning visual programs for public spaces in their towns. What guided municipal administrators in undertaking the task of commissioning shared civic infrastructures, such as city walls, commerce facilities or prisons? And how did artistic techniques, concerns, and discourses play into communal rulership? Papers that explore these or related questions across late medieval cultures and urban centers are welcome to apply.

(4) Stone Connects – Building Guild Networks from the Middle Ages to the 19th Century

Katja Schröck

The medieval large-scale construction sites of church buildings were not only places of artistic and craftsmanship production but also hubs of complex personnel and material networks. The supra-regional networks of builders´ huts enabled the transfer of knowledge, design models, and technical solutions, as well as the mobility of master builders, stonemasons, and sculptors. The construction sites of the Ulm and Bern Minsters exemplify an artistic and craftmanship practice that was interconnected far beyond their respective locations. Already in the Middle Ages, close professional contacts between the construction sites can be documented – this axis was revived in the 19th century.

However, the continuity of these guilds was often abandoned in the late Middle Ages for various reasons. During the long 19th century, various completion efforts led to a return to the tradition of building guilds.

This section examines, among other things, the personnel, material, and ideological/conceptual connections between construction sites as a model for reexamining the dynamics of medieval art production in terms of "work" and the continued or resumed structures: as a cooperative practice, as a socially embedded processes, and as an object of social evaluation. The aim will be to understand how work processes, constellations of actors, and networks in medieval construction can be reconstructed – and how they were (re)constructed, remembered, and made productive in the 19th century.

(5) Ora et labora? Talking and writing about artistic labour in the Middle Ages

Bruno Klein

The value of physical labour was viewed ambivalently during the long period of the Middle Ages: According to Max Weber, it was only in the late Middle Ages that precursors of the ‘Protestant ethic’, which sees work as the essential content of a fulfilled life, developed from a rather negative assessment of work in antiquity.

The verb “laborare” (Latin: to labour, to struggle) hardly appears in medieval artists' inscriptions, and even in early modern Paragone, intellectual labour was still given priority over physical labour, in line with the tradition mentioned above.

But how was artistic labour - from physical to mental - spoken and written about in the Middle Ages? After all, it was a reality, and it took up or absorbed a great part of manpower, for example in the construction of large cathedrals or town churches and their furnishings. Is this perhaps not adequately reflected in writings because the producers of texts did not belong or did not want to belong to the group of physically labouring people?

How and (from) when was such labour mentioned and named in treatises, textbooks, work contracts or corporate regulations, either directly or indirectly, e.g. in the definition of maximum working hours? Or in narrative sources such as those on the so-called cart cult, i.e. the collective physical labour, which was also similar to worship, for the construction of churches?

The section welcomes contributions that deal with this question specifically or systematically on the basis of individual or multiple sources. For example, by relating specific findings from building archaeology or ledger books on the amount of work involved to their further written mention and appreciation.

There is a particular interest in finding out whether and (from) when there was a special valuation of artistic labour and how this was defined. Sideways glances at pictorial representations, whose analysis could help to clarify these questions, are very welcome.

(6) Workways of Ornament

Irina Dudar

Ornament arises from the ordered and structured repetition of units. To make these requires, almost by definition, repetitive forms of work. These in turn can imply specialized tools creating repeatable forms: punches, stencils, and print blocks for instance. But ornament can also be created through the more-or-less exact repetition of simple gestures in defined intervals, in a process partly determined by the properties of the human body.

Although ornament has often been considered as the end result of a creative process, less attention has been paid to the working of ornament and its repetitive nature. Historically and still today, the former has served positivist goals such as workshop attribution and the distinction of individual hands; in more recent years, research has also turned to the skills involved in creating ornament, as well as to the sourcing and use of particular material. In addition, the cognitive and affective potential of ornament have been increasingly studied, but overwhelmingly from the reception side. This section prefers to analyse the cognitive dimension of ornament and its need for repetition from the perspective of those working, who act as the bridge between the idea and its material mise-en-oeuvre, the concept and the labor process. Objects of study from this perspective are repetitive gestures, concepts, and material processes, as well as the impact of repetition on the structure of labor.

In this section, we wish to consider how the repetitive forms of work implied by ornament both engender and spring out of embodied knowledge of materials, tools, and the body itself, and how this embodied knowledge in turn feeds into the cognitive work of planning ornament for any particular material circumstance.

We invite presenters to reflect on the following questions:

what happens at the intersection of planning and improvisation in the creation of ornamental fields?

how is improvisation practiced and repeated?

how do embodied knowledge and technique inform the planning process for ornament?

on the other hand, when is knowledge created from repetitive forms of work, including but not limited to the iterative planning of ornament in similar tasks?

when and how do the knowledge and technique gained from ornament-making inform the creation of figural forms?

(7) Aesthetic norms and technical reproducibility – aspects of serial production in Medieval Europe

Juliane von Fircks

Standardized work processes, which used identical materials, techniques, and forms to produce similar artifacts, were common in many medieval artists' workshops. A typical example of this are the workshops of Limoges, which, since the 12th century, have been producing a wide range of materially and aesthetically high-quality objects on a highly developed technological basis, intended for various functions in connection with Christian worship and courtly culture. The processional crosses, reliquaries, book covers, bishop's croziers, and decorative plaques produced in the Limousin workshops reproduced design standards that had been established over a long period of time. Characteristics associated with the enamel technique, such as colouring, figure formation and ornamentation, ensured that the artefacts were highly recognisable and this was probably responsible for the widespread sale of the objects throughout Europe. Similar phenomena can also be observed in the workshops of ivory carvers, silk weavers, embroiderers, goldsmiths, and seal engravers.

Only at first glance do the aspects of serial production in the workshops of the 14th and 15th centuries north and south of the Alps appear to be completely different. Precisely the same time when the names of individual artists were becoming widely known, painters and sculptors north and south of the Alps were particularly open to economizing their work. They experimented with the reproduction of heads, figures, compositions, and certain details of clothing and armor. They used cartoons and stencils, including mechanical fabric imitations such as pressed brocade. Sculptors experimented with artificial stone and clay, which allowed them to reproduce figures and compositions identically. In that era, the printing of patterns and images on fabric and paper was invented, which was to profoundly change the media landscape in Europe.

This section examines artistic genres and techniques from the High and Late Middle Ages in light of the following questions: What was the relationship between economized work processes and the appearance of the finished work? Were standardized procedures, including mechanical reproduction, used primarily to produce more effectively and in greater quantities, or was it also a matter of securing established aesthetic standards or reproducing certain “archetypes”? What was the relationship between effective repetition of form and style? How did the division of labor work in detail? Who supplied the designs, and what kind of quality controls were in place? Who was credited as the author? For which customer groups were the works intended, and how was sales organized? Were the artworks and artifacts in question also perceived as serially produced in their reception? Under what conditions could artefacts produced serially or using standardized working methods achieve an auratic effect and that status of unmistakable uniqueness in cult and social practice that Walter Benjamin described as the essence of the artwork in the pre-industrial age?

(8) Between Work, Science, and Wonder: Automata and the (In-)Visibility of Labor

Joanna Olchawa

Automata are among the most remarkable objects in the history of medieval art, science, and technology. Whether in the form of clocks, fountains, organs, steam machines, or figurative ensembles, these works seem to move on their own, produce sounds, or carry out complex processes. Driven by pneumatics, hydraulics, or finely tuned mechanics, they create the illusion of ‘work without workers,’ challenging fundamental notions of labor or (transcendent) creative force. While the underlying mechanisms are often hidden, work must still be done to set them in motion and maintain their operation. This, in turn, required highly specialized workshops. Automata thus create a rather ambivalent view of labor, blurring the boundaries between art and skill, and between work, science, and wonder.

This session focuses on the previously underexplored connection between automata (from the Latin West, Byzantium, and regions under Islamic rule) and labor between the eighth and fifteenth centuries CE. It is particularly interested––though not exclusively––in: 1) the ‘working’ mechanisms such as gears, weights, pulleys, and other technical components; 2) the social positioning of those involved in their creation, and thus the question of who designed, built, and maintained these objects; 3) the symbolic implications of labor made visible or hidden by automata, and how these relate to contemporary notions of human, mechanical, and ‘divine’ efficacy; and 4) periodization, as automata are often associated with the Early Modern period or Modernity, even though they were known, admired, and integrated into various visual and material contexts and discourses in the Middle Ages.

By combining approaches from the history of technology, social history, and visual culture, this session aims to explore the phenomenon of automata as a focal point of medieval concepts of labor, while also offering a new perspective on art-historical debates concerning the relationship between art and technology, nature and culture, craft and imagination, and play and seriousness.

(9) Working with Fire: Collaborative Art(Work) across Pyrotechnologies

Hallie G. Meredith

Fire, long regarded as one of the fundamental natural forces and elements, is universallyaccepted as vital to human life. Mediated by human action, the controlled application of fireunderpins a vast array of historic technologies, from clay crafts (baked bricks, clay pipes, pottery)to metal production (copper alloy, gold, silver) and silica-based arts (faience, glass, porcelain). Acrucial aspect of craftwork involving fire is the transformation produced. Transformative craftschange raw materials through pyrotechnology or chemical processes to create a new material.The fundamental question that underpins this proposed session concerns the interactivitybetween craftworkers and the elements - not only fire but also air, water, and nature writ large -during the dynamic late Antique/early Medieval era (c. 4th-6th centuries CE) and throughout theMedieval period.The focus of this session will be the art(work) that embodies and communicates suchinteractivity. Pyrotechnic industries, for example, relied on tools, such as braziers, furnaces andkilns (often made of earth), that served to some extent as a means of containing, gradating, andmanipulating fire, which cannot happen without air. These industries included the production ofceramics, encaustic, glass, lime, metal, and even the heating of baths, among others. Scholarsstill commonly approach pyrotechnologies as isolated and independent, but many of these werelikely interconnected activities, with overlap in terms of labour, skill sets, tools, locations, as wellas marketing and trade. The possibility of such networks is relevant to the burgeoning study ofinter-industry relations or cross-craft.The constellations of collaborative making may include the relations between craftworkers, theimagined exchange between a human labourer and a divine creator, or the interaction between ahuman worker and one or more non-human, engineered materials. Inter-industry relations andhow they may have impacted the division of labour and the notion of a specialist are alsopotentially fruitful areas of enquiry. The overall goal of this session is to highlight the place ofthe materials themselves in shaping the realities of craftwork - and craft society - in earlyMedieval history, bringing to light transformations both within and beyond.

(10) Working on the Object: Reuse and Transformation as an Art Historical Approach

Carolin Gluchowski

When is the work on an object finished? When can an artwork be considered complete – with the final brushstroke? With the payment of the invoice? Upon delivery to the patron? Or does a new phase begin after the work on the object is completed – namely, the work with the object, once it enters into use?

The reuse and transformation of artworks is not a modern phenomenon but rather an anthropological constant that can be observed across different cultures and historical periods. In the Middle Ages, reworking, adapting, modifying, integrating, expanding, or reducing objects was a common and accepted practice – driven by pragmatic, aesthetic, religious, or symbolic motives. In recent years, art historical scholarship has increasingly turned its attention to this phenomenon, using conceptual frameworks such as reuse, reframing, deframing, recycling, appropriation, or resemanticization.

This proposed panel seeks to shift the focus toward the ongoing work on the object itself and to enrich theoretical and terminological debates through concrete case studies. We invite contributions that approach the topic from the perspective of the object and centre on specific practices of alteration and transformation:

What kinds of changes can be traced materially on the object? What remains stable, what is removed or added? Which intermaterial relationships are interrupted, redirected, or created? And which methodological tools are available to art historians to detect, reconstruct, and analyse such traces of work?

These questions also prompt an investigation of the contexts in which reworking took place: In what social, religious, or economic circumstances was work on an object resumed or continued? What motivated premodern actors to alter an object? Who carried out this work – and how were these individuals perceived: as artists, artisans, creators, or restorers?

The aim of the panel is to take the forum’s theme – work – literally: as a visible, reconstructable, and contextualisable activity enacted upon medieval objects. In doing so, the panel contributes to ongoing discussions surrounding processes of making, object biographies, authorship, (inter)materiality, and the social embeddedness of artistic production.

(11) Working with Ivory – Material, Craftsmanship, Trade

Svea Janzen

Questions about work processes – concerning producers, techniques, and material-specific manufacturing possibilities – occupy a central position in the research of medieval ivory carvings. Over the past century, stylistic analysis has allowed for the geographical and chronological classification of numerous groups of artefacts, as well as the reconstruction of individual artists’ or workshops’ oeuvres. Based on these foundations and motivated by the growing interest in the artefacts of material culture within the ‘global Middle Ages’, ivory research has recently gained fresh momentum, leading to the expansion and refinement of questions and methods. The subject of ‘work’ with this precious raw material and its more accessible alternatives remains a central focus of scholarly investigation:

Research on sources and the trade of materials such as elephant tusk and walrus ivory has significantly advanced our understanding of major developments in ivory art, while studies of historical sources and the evaluation of archaeological contexts have provided a more nuanced picture of ivory-working trades and their clientele. Object-centred investigations into specific material processing have provided insights into production methods, ranging from custom work to serial production. Moreover, the incorporation of previously understudied everyday objects (mirrors, combs, etc.), as well as artefacts of lesser value made from more affordable surrogates (buttons, dice, etc.), offers significant potential to reconsider medieval everyday culture and the organization of craftsmanship. All these approaches inspire for further research; especially, in a research landscape traditionally divided into ‘Romanesque’ and ‘Gothic’ periods, the potential to address questions through a comparative perspective spanning the entirety of the Middle Ages still remains.

In this context, the session calls for contributions that explore all aspects of working with ivory and related organic materials (walrus and narwhal tusks, bone, antler, and horn) during the Middle Ages. Possible topics for discussion include: trade and availability of raw materials; production techniques and traces of work; steps of processing between different locations and crafts; output of individual workshops; the work organization and collaboration with other crafts; resources and use of the valuable raw material; ivory carvers operating within urban centres, courts, and ecclesiastical institutions; market for ivory artefacts (including patrons, clients, and intermediaries, etc.); and other related themes. Contributions are welcome from art historians, conservators, historians, and archaeologists alike.

(12) Coworking spaces – Collaborative working in the Middle Ages

Julia von Ditfurth

In contemporary coworking spaces, professionals from various fields come together to work in an inspiring working environment and to benefit from mutual exchange. A similar dynamic could already be observed in the workshops of Gothic cathedrals, where craftspeople from various trades shared a platform that encouraged interdisciplinary dialogue and laid the groundwork for artistic innovation. Although ‘Romanticism’ recognised the value of such collaboration, academic discourse split the ‘fine’ and ‘applied’ arts and overlooked their interplay in favour of isolated, media-specific approaches.

This section will explore the various forms of collaboration between stained-glass painters and other visual arts, examining the communicative coordination processes and reflecting on both its potential and limitations.

We welcome contributions that address the relationship between stained glass and architecture: As a medium inherently tied to architecture, stained glass required close coordination with architects and stonemasons. The visual correspondence of architectural framing in stained glass painting to the built architecture invites reflection on the exchange of designs. What role did stained-glass painters play in the creation of new decorative forms, and how did this involvement influence their working practices?

Submissions focusing on the subject of design and execution are particularly encouraged. Stained glass serves as a prime example of a transfer process, as its realisation always requires a preliminary design. While both design and execution were originally undertaken by a single person, growing specialisation in the late Middle Ages saw panel painters increasingly entrusted with the design. In regions where close collaboration between panel and stained-glass painters is documented (Strasbourg, Nuremberg and Augsburg), the active role of panel painters in execution and the adoption of painting techniques warrants further investigation. Can traces of this cooperation be detected in the surviving works through modern art-historical or technological analysis? What role did guild regulations play in shaping workshop practices? What rules governed collaboration, and where were boundaries clearly defined?

Finally, various late medieval written sources reveal that stained-glass painters often also worked as panel painters or manuscript illuminators. What artistic interactions took place across these media, and what was the specific organisational structure of such workshops?

(13) The Work of Goldsmiths

Rebecca Müller

At first glance, we seem to have ample information with which to understand the ‘work of goldsmiths’: the objects that come down to us are increasingly being examined in the spirit of an interdisciplinary ‘technical art history’, and texts such as the Schedula diversarum artium provide us with sources that encompass, among other aspects, practical and socio-artistic dimensions. Yet, outside of the few touchstone sources and objects, one can identify surprising desiderata when it comes to the actual conditions of goldsmiths’ work, particularly for the period before 1300: questions persist regarding training, degrees of specialization, geographical fields of activity, the procurement of materials and tools, and labor organization – all compounded by the often multifaceted nature of goldsmithery in terms of techniques and materials. This section invites both case studies and broader reflections on these themes, including from the fields of Islamic and Byzantine art history.

Possible topics include: What conclusions about the working process may be drawn from the objects themselves – whether from materials, techniques, toolmarks, alterations, etc., or from images and inscriptions? How did goldsmiths themselves give directives (e.g., offset marks), and to whom: the assembler or the user? Why might an object have been reused, discarded, or left unfinished? Historically, how have traces of the working process been interpreted? Also of relevance are the media involved in fabrication that remained separate from, or ‘invisible’ in relation to, the resulting object (e.g., drawings, fillings used in repoussé work, wooden cores).

How informative are written sources with respect to the production of goldsmiths’ work and its social contexts, such as the organization of workshops, the division of labor, and associated technical procedures? Particularly crucial is the issue of whether changes can be identified between the ‘Middle Ages’ and the ‘early modern period’, and thus whether the attribution of epochal differences is justified – a question that comes to bear also on the evaluation of goldsmiths’ art.

Submissions are welcome from all fields related to the work of goldsmiths, and especially from museums and conservation science.

(14) Textile Work in the Middle Ages: Production Processes between scientiae mechanicae and artes liberals

Corinne Mühlemann

In the Middle Ages, textile work was among the most complex and economically significant branches of production. Situated at the intersection of artisanal specialization, artistic sophistication, economic relevance, and social attribution, it offers a rich field for the art-historical analysis of textile artefacts. This session addresses textile production from two interrelated perspectives: on the one hand, within the framework of historical systems of knowledge such as the scientiae mechanicae, and on the other, through material traces that provide insight into manufacturing processes.

Knowledge about raw materials, their processing and refinement through dyeing and other techniques goes back to antiquity and are recorded in texts such as Pliny the Elder’s “Naturalis historia” and Isidore of Seville’s “Etymologiae”. In the 12th century, Hugh of St. Victor defined lanificium – the science of textile production – as the first of the seven scientiae mechanicae, in parallel to the seven artes liberales, in his “Didascalicon”. Additional insight into textile production processes is offered by written sources from the Mediterranean, including documents from the Cairo Geniza, ḥisba treatises, and the «Trattato dell’Arte della Seta».

These sources provide detailed information about the complex workflows involved – from the procurement and transformation of textile fibers to the production and finishing of yarns, and finally to the creation of textile surfaces, such as woven fabrics or tapestries. These pieces could be the final products in their own right or further processed with increasing complexity – through painting/printing, embroidery, and/or tailoring – into furnishings, garments (both liturgical and ceremonial), or close-fitting clothing.

Counting and measuring were essential at every stage of production: while counting was indispensable in weaving (e.g. in setting up looms), precise measurements became especially relevant in trade and in tailoring. The variety of medieval metrological standards and the impressive lengths of woven pieces (coupons) point to specialized technical knowledge and a sophisticated division of labour. This is particularly evident in high-quality artistic products that employ seemingly restrictive techniques such as weaving. In this context, creative ambition can also be seen as a form of playful engagement with the artes liberales, e.g. in ‹free› techniques such as embroidery through a counted-thread or repetitive structure. Such choices may reflect a nuanced self-image on the part of the makers.

The session jointly developed by Caroline Vogt and Corinne Mühlemann invites contributions that explore material evidence and written sources shedding light on production processes, division of labour and the visibility of the artisans and artists involved in textile production, and their social status in medieval Europe and the Islamic world. We also welcome papers on the historiography of the field, especially regarding the perception and appreciation of textiles and their makers in art-historical discourse.

(15) Temposensorial Settings – Zeit und Sinnlichkeit im Kontext mittelalterlichen Arbeitens

Hanna Christine Jacobs

Against the backdrop of the fast-paced work of today's era of rationalization, digitalization, and AI, where routine tasks are completed with great haste on the one hand and work-induced flow experiences are celebrated on the other, this session asks about the conscious experience of time and sensuality in the context of medieval work and work-free “festive times” and their reflection in artworks of this era.

First, questions of time perception will be addressed: How can the conscious experience of time be described against the backdrop of the close connection between work and daily structure? Does the design of the artifacts reveal anything about the value of the category of time within their production, function, or reception? Where, how, and when do the works of art refer to the experience of time? To what extent do elaborate objects (such as hard stone carvings or goldsmith work) reflect the enormous amount of time that went into their production, and does this influence their reception? Does the temporal limitation with which objects are used in the context of ritualized actions influence their form? Can the traditional media concept of art history be expanded to include temporal, fluid, situational, and processual aspects?

Secondly, we focus on the aspect of sensuality in connection with the working process itself and with rituals that can be understood as a contrast to everyday work: How is the sensual experience taken into account in specific situations of use during production? How does it determine the material development of objects? How do multisensory material affordances guide the work on the pieces? And how and by what means do the objects become part of rituals that are staged as pauses from recurring work? How do those people who are not allowed to perform the liturgical or ceremonial acts participate through the craftwork they put into the objectsand their festive activation?

Thirdly, the section also wants to ask what opportunities for insight practical, sensually experienceable work with 3D printing, virtual reality, and other digital media offers for art historical research. Under these and other aspects of “temposensorial settings”, the section will examine the “working” steps involved in the production, use, and reception of medieval works of art.

(16) The object in focus – on the contribution of object autopsy to art historical research using goldsmithing as an example

Stephan Patscher

The surviving works of art from the Middle Ages also include works of goldsmithing. They are often characterised not only by the use of high-quality materials, but also by a high level of craftsmanship. Due to the relative resistance of precious metals and many decorative materials to degradation and corrosion processes, they are comparatively well preserved. This also applies to tool marks and other traces of manufacture and to signs of wear and tear caused by the use of the object in question. Accordingly, these objects of medieval treasure art can be subjected to an autopsy in order to scientifically determine the materials, identify the construction and recognise and analyse traces of manufacture and use.

But in what way can such an interdisciplinary autopsy contribute to actually expanding the level of art historical knowledge about an object or group of objects? To what extent does it allow conclusions to be drawn about the production process and thus about the technological and technical knowledge and skills at the time of creation? To what extent is it suitable for helping to resolve art historical disputes, for example regarding the integrity of an object, its use or even its place of origin?

Welcome are contributions that can show exemplary how a broadly based autopsy of an individual object or groups of objects can answer questions from art studies such as those mentioned above.

(17) Working on the Original, Engaging the Public: Medieval Craft Traditions in the Contemporary Museum

Katja Triebe

In the Middle Ages, artists translated complex theological ideas into tangible forms, shaping key themes through their craftsmanship. Today, museums face both familiar and new challenges when presenting these works. Most medieval artefacts are fragile, often fragmentary, and displayed outside their original contexts within art-historical frameworks. At the same time, museums must justify their work to funders, sponsors, and increasingly diverse audiences with varying expectations.

Many visitors lack prior knowledge of medieval art. Religious imagery, liturgical functions, and theological content are no longer self-evident. Meanwhile, medieval themes are flourishing in popular culture –including video games, films, TV series, and novels – often with increasing historical sophistication. These media also influence how the Middle Ages are perceived within the museum context and are already being strategically employed to offer accessible yet substantively relevant pathways into medieval art. In this process, materials, historical working techniques, and tools often come to the fore in object interpretation. Might it be that artistic craftsmanship is what connects us across the centuries with sacred art?

Current exhibition practices vary widely, ranging from permanent displays and open storage to blockbuster shows and small-scale exhibitions. These presentations are often situated in dialogue with artworks from other cultures, contemporary art, and broader global discourses. Moreover, the museum's own working processes – such as provenance research and conservation – are becoming integral parts of the narrative. New strategies emphasise participatory, inclusive, and interdisciplinary approaches, supported by emerging scholar initiatives and cross-institutional collaborations.

Against this backdrop, the question arises: which aspects of medieval art are (or should be) conveyed through this diversity? Is this development beneficial or overwhelming – and for whom?

This session aims to examine how museums work with medieval art in order to explore potential answers. What constitutes effective mediation of medieval art today? Central to the discussion are questions of appropriate modes of presentation amidst the tension between conservation demands, religious sensitivity, digital transformation, and scholarly responsibility. For whom, and how, should museums operate today?

We warmly welcome practice-based reports, conceptual approaches, analyses, and visions!

(18) Recasting Byzantium: Tracing Work and Craftsmanship in Popular Culture

Antje Bosselmann-Ruickbie

This session addresses how Byzantine work and workmanship are reimagined in global popular culture across a variety of visual and literary media – including film, graphic novels, comics, video games, music albums, stage design, and costumes – and how they contribute to contemporary conceptions of Byzantium. These media often constitute the primary point of access to historical periods for the general public.

Central to our inquiry is the question of valuation: are these traces of work portrayed with historical specificity and contextual nuance, or are they freely interpreted? Do such representations reflect scholarly engagement with Byzantine arts and crafts, or do they uncritically perpetuate orientalist tropes, aesthetic eclecticism, and romanticised visions of a “lost” empire?

A compelling case in point is the Netflix series Vikings: Valhalla (2022–2024), which follows the eleventh-century Norseman Harald Hardrada to Constantinople. While certain architectural and topographical elements suggest engagement with accessible scholarly reconstructions, the depiction of material culture – and the traces of the elaborate workmanship behind it – from costume and military equipment to interior design and furniture, largely presents a hybridised collage of Byzantine, Western, Islamic, Ottoman, and modern design traditions, replete with clichés of oriental decadence and eroticism. The series thus oscillates between portraying Byzantium as historical reality and as medieval fantasy.

This example reveals the wide scope of artistic license in popular culture – arguably a form of craft in its own right – and raises critical questions about the dichotomy between historical accuracy and authenticity. This panel considers how Byzantine arts and crafts shape cultural memory, and how knowledge of material culture circulates, mutates, and acquires meaning beyond academic frameworks – informing aesthetic perception and memetic transmission. The growing use of Byzantium as a reference model reflects rising interest, but this contrasts with limited public knowledge – leaving ample space for imaginative, politicised, or ideologically charged projections. By including both visual and literary media, we highlight the breadth of this still underexplored yet increasingly relevant field.

Proposals from advanced students and scholars at all career stages are expressly welcome.

(19) Images that Operate: Representing Medical Knowledge & Labor in Medieval Scientific Manuscripts

Reed O’Mara

In medical texts like Roger of Salerno’s (c. 1080–1119) Surgery or John of Arderne’s (1307–1392) Fistula in ano, images of doctors and their patients—or simply parts of their bodies—visualize ailments and procedures in vivid detail. The roles such images as well as accompanying diagrams play in medieval scientific, especially medical, manuscripts from the later Middle Ages have yet to be fully analyzed. Their contextualization within the increasing professionalization of surgeons and other medical practitioners in the Middle Ages also remains to be seen. How these images and diagrams “work” in relation to and beyond the texts they accompany, and what they meant for the standardization of medical knowledge, including the development of its verbal and visual terminology, has only recently come under art historical investigation. The relationship between word, image, and the actual labor of medical practitioners and surgeons requires further study. Therefore, this session welcomes papers analyzing the creation, use, and reception of illustrated scientific works like, but not limited to, Fistula in ano, Galenic surgical treatises, and Robert of Salerno’s Surgery. Papers that investigate the shared medical traditions of Latin and Hebrew medical manuscripts are especially encouraged.

Guiding questions for papers include the following: how do the labors of the author, scribe, artist, and physician-reader in illustrated medical manuscripts all intersect? What are the limitations of using the term “illustrated” to describe such volumes? What is the necessity or value of having such robust and frequently repetitive image programs? What is the divide between the diagrammatic and the imagistic? What is the significance and purpose of diagrams within such volumes? What role does gender play in medical representation? How do the images and diagrams themselves perform and operate? How are patients and doctors alike figured and conceptualized within these image cycles and what is the cultural backdrop of these representations?

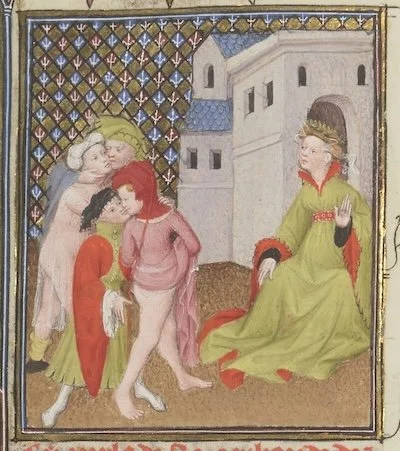

(20) Labours of the Month – The Occupational Calendar

Gia Toussaint

In the rural society of pre-modern times, work was largely linked to the cycle of the year with its seasons and their specific climatic conditions and challenges. A fixed system of activities structured the entire year from January to December and made work a cyclically recurring activity. These activities are visualized in the "labours of the month", images that portray the work that had to be completed in a specific month, such as the grape harvest in September.

Labours of the Month cycles have been preserved in manuscripts since Carolingian times. Their integration into liturgical and paraliturgical manuscripts indicates the importance of the calendar structured by Christian festivals and saints' days with specific work associated with them. While work came to a standstill on high Christian festivals, saints' days were proverbially associated with certain activities (e.g. ‘St. Martin brings the cattle into the stable’ on 11 November). In this way, the rough monthly division was thoroughly organized down to the smaller units of (saints') days and was additionally linked to the favourable influence of certain saints, whose blessings were implored for the work to be done. In addition, work was linked to cosmological influences, as each month was dominated by a specific sign of the zodiac and an individual position of the moon and sun, whose specific powers had an effect on nature and humans. Work, seasons, celestial bodies and saints' days formed a fixed unit that had to be recognized and implemented anew throughout the course of the year.

Calendars illustrated with monthly tasks were effective teaching aids and offered practical and religious guidance. They placed working people in a God-given order in which every job had its place. However, this section will not only discuss calendars in manuscripts, but also examine the function of monthly tasks on church portals and furnishings (e.g. Chartres). How is work depicted in the image sources: as drudgery, as a source of meaning, or even as pleasure? Was the work depicted adapted to specific groups of recipients? Were only “godly” activities worthy of being depicted, or were trades on the margins of society also represented? How relevant are the accompanying texts in classifying the depictions of work, or can the images stand on their own?

(21) Tricks of the Trade: The Visual and Material Dimensions of Medieval Sex Work

Rowanne Dean

(sponsored session ICMA)

In his vita of the “saved prostitute” (turned “crossdressing” ascetic) St. Pelagia, James the Deacon describes how Nonnus, a bishop of Antioch, reproaches his male religious peers for averting their eyes from the courtesan’s beauty and bodily adornment. He implores them to instead comprehend her as an exemplative lesson: just as Pelagia lavishes time and attention to the work of decorating her body for her lovers, so too, should the bishops prepare their souls for their eternal Bridegroom. In the Golden Legend, Pelagia is similarly said to have “painted herself so meticulously” that she should be brought forth on the day of Judgment against those who take little care to please their heavenly Spouse. Though here a courtesan’s cosmetic labor is analogized in positive terms, the work involved in providing commercial sexual gratification was, by turns, merely tolerated and actively vilified in medieval theological, literary, and legal discourse. Building on the classic studies of Ruth Karras, Leah Lydia Otis, and Jacques Rossiaud, among others, recent scholarship has considered the visual dimensions of medieval sex work in various ways. Judith M. Bennet and Shannon McSheffrey have discussed female “crossdressing” in late medieval London, which was associated with sex work; Jess Bailey has analyzed depictions of disabled sex workers in the drawings of Urs Graf; and Jelle Haemers has examined the material culture of prostitution in the late medieval Southern Low Countries. This session aims to further explore the question of how sex work was thematized in medieval material and visual culture. How were sex workers represented? How were they thought to represent themselves? And how were viewers implicated in their visual apprehension? Paper proposals might explore the following topics: the visual marking of the prostitute’s body through garment regulations and sumptuary laws; the question of sex work as a craft or trade; representations of brothels; notions of illusion and deception in discussing sex workers; relationships between sex-work and (visible) gender non-conformity; the idealization and/or vilification of (feminized) sex workers’ beauty; sex work and cosmetics or bodily adornment; iconographic traditions such as the Prodigal Son with prostitutes or the Whore of Babylon.

(22) “By the sweat of your brow you will eat” and create(?): Ritual and creative implications of medieval representations of the labours

Vladimir Ivanovici

Over the twelfth century, labours associated with each month of the year began to be depicted in prominent locations of Christian buildings and on key liturgical furnishings, namely cathedral portals and windows, baptismal fonts, and church pavements and columns. Replacing or accompanying depictions of the zodiac constellations – for which Christians had continued to use the polytheistic imagery inherited from the Romans – the new images of the labours signalled a changed perspective on work, as various types of physical work were presented as joyful activities. Past research focused on the iconographic formulas and explored their socio-political implications, as instruments meant to appease social unrest and confirm the status quo of medieval communities. This session invites papers that explore instead the ritual and creative dimensions of the images. Considering their locations and the rituals performed there, papers should inquire how the representations were integrated into or contributed to the experience, whether strictly religious (i.e., baptism) or the varied, civic and religious celebrations performed in front of cathedral portals decorated with images of the works. In addition, we invite contributions that investigate how the new outlook on work that the images promote might have influenced the creative efforts that characterise this period. In particular, we are interested to see how the transformation of the symbol par excellence of humanity’s fall – i.e., the physical labour required of Adam (Gen. 3.19) – into a testimony of one’s contribution to the cosmic order established by God inspired the creative efforts of this period. Ultimately, this session invites us to ponder whether the development and dissemination of the Gothic style would have been possible without a changed perspective on work, given that Suger’s St. Denis already contained the representation of the monthly labours.